Ian Cero · Munmun De Choudhury · Peter A. Wyman

Received: 13 February 2023 / Accepted: 8 June 2023 / Published online: 21 June 2023

© The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany 2023

Purpose The structure of relationships in a social network affects the suicide risk of the people embedded within it. Although current interventions often modify the social perceptions (e.g., perceived support and sense of belonging) for people at elevated risk, few seek to directly modify the structure of their surrounding social networks. We show social network structure

is a worthwhile intervention target in its own right.

Methods A simple model illustrates the potential of interventions to modify social structure. The effect of these basic structural interventions on suicide risk is simulated and evaluated. Its results are briefly compared to emerging empirical findings for real network interventions.

Results Even an intentionally simplified intervention on social network structure (i.e., random addition of social connections) is likely to be both effective and safe. Specifically, this illustrative intervention had a high probability of reducing the overall suicide risk, without increasing the risk of those who were healthy at baseline. It also frequently resolved stable,

high-risk clusters of people at elevated risk. These illustrative results are generally consistent with emerging evidence from real social network interventions for suicide.

Conclusion Social network structure is a neglected, but valuable intervention target for suicide prevention.

Keywords: Social network, Intervention, Suicide, Target, Network structure, Cluster, Simulation

The network of relationships in which people are embedded is intimately connected to suicide risk and protection. In this way, social networks are themselves foundational to suicide prevention science. Starting with Durkheim’s anchoring work linking density of social ties and suicide mortality rates [1], the importance of social networks has now been replicated in multiple populations, methodological approaches, and suicide-related outcomes [2–8]. In work using more modern research methods, experimental manipulations of social ties have been shown to affect the development of subsequent suicidal ideation [9] and interventions that enhance social network bonds shown to reduce risk of ideation, attempts, and even mortality [10].

This work has powerfully impacted interventions for suicide risk across the prevention continuum, from universal population-oriented programs to clinical interventions for

acutely suicidal individuals [11–13]. Indeed, most current

interventions now explicitly address the social health of their recipients (e.g., perceived social support and social skills

competencies) and with growing empirical support [14, 15]. However, few if any current interventions directly target the structure of the natural social networks in which those individuals are embedded. That is, they may aim to strengthen an individual’s capacity to interact with their network (e.g., draw support), without targeting the characteristics of the surrounding social network that transmit their own substantial risk and protection. This is important because social network structure is non-random [16]. Networks are formed and evolve through the individual affiliative choices their members make, and in turn, those members influence each other through those relationships [17]. In addition, because these choices tend to follow a particular course, so too does the evolving structure of the network and its reciprocal influence back on the individuals who comprise it [18, 19].

Ian Cero

ian_cero@urmc.rochester.edu

1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical

Center, 300 Crittenden Blvd, Rochester, NY 14642, USA

2 School of Interactive Computing, Georgia Institute

The pattern of relationships (i.e., structure) of a social network is thus itself a worthwhile object of systematic study, and in turn a compelling candidate for intervention. We, therefore, introduce social network structure (i.e., the pattern of relationships in a network) as an explicit intervention target for suicide prevention science. We begin with (1) a brief introduction to social network terminology and the distinction between social factors and social networks. Next, (2) we present a simplified quantitative model showing that even relatively simple interventions on network structure are likely to have protective effects. Finally, (3) we summarize emerging empirical evidence that social network structure is responsive to intervention, and that those interventions have been able to reduce suicide-related outcomes in randomized trials.

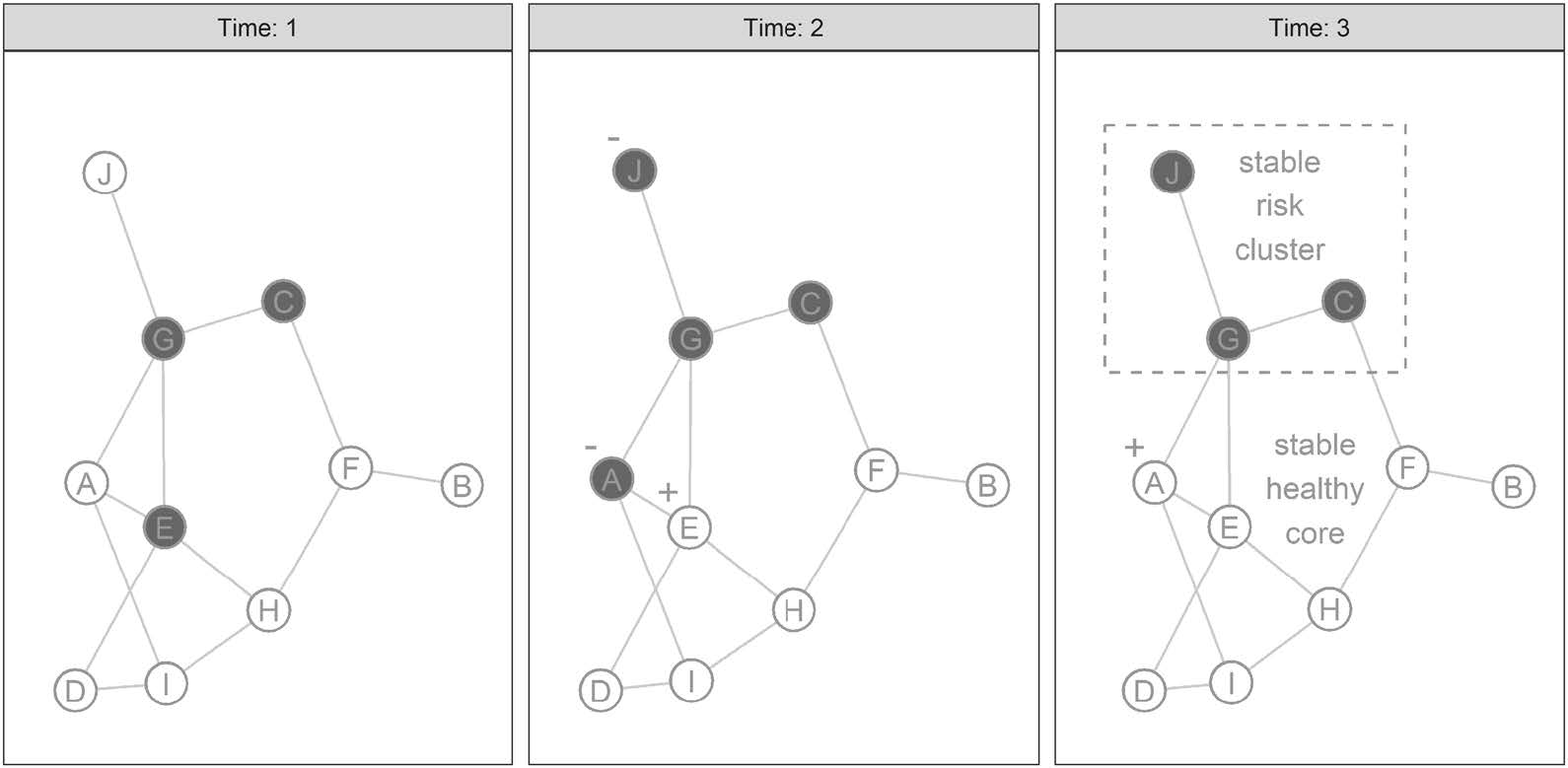

Fig. 1 Evolution of a stable suicide risk cluster in a simulated social network. Dark-shaded nodes represent people at elevated risk for suicide. Light-colored nodes represent people in a healthy state. The “+” symbol indicates a node’s health has improved since the last time point and the “-” indicates a decline in health. Nodes are labeled alphabetically for clarity. Changes in node state are determined by a simplified quantitative model, in which nodes seek to adopt the most recent state (at last time point) of at least 2/3 of other nodes to whom they are connected. If no recent 2/3 majority is present among their immediate network neighbors, they make no change. By the third time point, the entire network is stable and no further changes are possible according to these rules.

Social networks are collections of people and their relationships. These networks have content, which includes both the attributes of each person in the network (e.g., age, attitudes, and behavior) and the attributes of each relationship (e.g., type of relationship and frequency of interaction). Networks also have structure, which is the pattern in which those relationships are arranged—the constellation of who has relationships with whom. With this structure, it is possible to characterize not only an individual person’s position in a network (e.g., center vs. periphery), but also to compare different networks to each other. For example, some networks are highly centralized, with many ties concentrated in a smaller number of people, while others are more decentralized, with a more even distribution of ties across many people. In this way, two networks can have identical content (e.g., political attitudes of individuals average relationship age), but distinct structures. As we will show below, a network’s relationship structure is capable of affecting suicide risk and protection— over and above that same network’s content.

By convention, the people in a social network are called

nodes or vertices and their relationships are called ties, links, edges, or (less commonly) arcs.1 As implied above, both nodes and edges can have various categorical and continuous attributes; however, there is one edge attribute that is always important, directedness. If a relationship has meaningful asymmetry or direction between the people who comprise it (e.g., parent-of-child and unrequited love), then it is called a directed edge. If the relationship is best understood as non-directional or reciprocal (e.g., siblings and spouses), the edge is called undirected. Like in Fig. 1, social networks are often visualized by depicting nodes as points or circles and edges as lines. Lines ending in an arrow typically denote directed edges (e.g., parent –> child) and lines without arrows denote undirected ones (e.g., sibling 1 — sibling 2). For readers interested in a more comprehensive treatment of social network analysis, there are many exceptional texts worth consulting [18–23].

1 In this discussion, ‘node’ is always equivalent to ‘vertex’ and so the terms are used interchangeably. The same is true for ‘ties’, ‘links’, ‘edges’ and ‘arcs’, which are also used interchangeably. Readers seeking to further their exploration of social networks beyond the current discussion will find these conventions can almost always be safely assumed in other papers too. Exceptions exist, (e.g., ‘arc’ is occasionally reserved for directed relationships, like parent to child), but they are especially uncommon in the recent literature.

How is the social network approach distinct from existing work on the social variables that influence suicide risk and protection? In typical studies in suicide prevention, individuals’

social perceptions are the primary variables of interest (e.g., perceived burden and belonging, and perceived social

support). This individual-centric survey approach captures an important dimension of social experience (i.e., an individual’s

broad impression of their social life). However, it excludes information about broader social structures in which an individual is embedded, which are in turn known to influence their well-being and health—including suicide risk. For clarity, we, therefore, refer to the traditional individual-centric approach to suicide as studying social perceptions and the approach focused on the structure of relationships as studying social networks.

This distinction has implications for intervention. In framing social environments and experiences in different ways, the social perception and social network approaches tend to imply different kinds of interventions to prevent suicide-related outcomes. For example, understanding social isolation as a personally perceived risk factor implies solutions that alter that person’s perceptions or their behavior in some way (e.g., challenging negative beliefs, social skills training, and instructions to seek out old friends). In contrast, understanding social isolation as a feature of network structure (i.e., missing social ties) implies solutions involving intentional enhancement of that structure (e.g., group level interventions to repair old ties or create new ones).

Attentive readers will observe that the distinct approaches in this example are not technically incompatible, in fact they are likely complementary. For example, the network interventions we discuss in the final section generally target both the development of individuals’ social skills, at the same time that they develop structure of the surrounding network. Our point is thus not that social network structure should replace social perceptions as intervention targets. Rather, our point is that social network structure is a unique and valuable intervention target in its own right.

Empirical research has underscored two recurring structural patterns of social networks that are especially relevant to suicide risk and prevention, as well as some initial causal explanations for why they so often reappear. Specifically, research has shown that people at elevated risk for suicide-related outcomes are (a) disproportionately clustered with one another and (b) and are less integrated into their broader networks [2, 3, 7, 24–27].

The tendency of people to be connected to others with similar characteristics is called assortativity. This observation is known to be caused by at least three processes, all of which are likely active at the same time [3, 25]. The first is social influence, in which people start to emulate those with whom they are already connected (e.g., by normalizing suicide, or through adoption of an upstream risk factor like substance use). The second is homophily, in which people

(consciously or unconsciously) seek to form new connections with those who are more similar to themselves. The third is a shared environment, in which people who occupy the same environment (e.g., workplace and neighborhood) tend to know each other because of their proximity and tend to be similar because they are both affected by that environment (e.g., comparable risk of layoffs and availability of illicit substances).

Taken together, these forces yield a plausible explanation for the recurrent assortative clustering of suicide risk in social networks: people with elevated risk may unconsciously influence their friends toward similarity, the new friendships they do form will tend to be with other at-risk people, and they occupy environments that are more likely to prompt everyone toward elevated risk. Conversely, the opposite is true for their healthier peers, who are influenced toward greater health by their already healthy friends, the people they form new friendships with will tend to be healthy, and they disproportionately occupy healthier environments.

Tendency toward isolation: is also likely affected by underlying network processes. In addition to the fact that isolation likely increases risk for suicide through thwarting of basic relational needs [28], it is also plausible that the experience of suicidal thoughts and behaviors can influence an individuals relationships in way that tends toward isolation. To explain, suicide-related risk is relatively uncommon in the general population. Since people tend prefer connections with similar others, elevated suicide concerns may increase the likelihood that a person’s existing connections with healthier peers dissolve at higher rates than average.

In addition, because most peers are generally healthy with low suicide risk, this leaves many fewer options available for replacement connections. For example, even the concerningly high 8.9% attempt rate among high schoolers still also implies that greater than 90% of that same population did not attempt suicide over the same period [29]. Comparable trends are observed for suicide ideation, in which an even higher 18.8% rate of students ‘seriously considering

suicide,’ also implies approximately 80% of the same population did not. This pattern holds outside of adolescence too, as evidenced by relatively low rates (by proportion of total population) of suicide-related outcomes across the general

United States population [30].

Moreover, the connections that are available will tend to

be among others who are themselves more isolated, leading to fewer downstream connections (e.g., those that might arise from meeting friends of friends). Combined with well-documented person-level factors (e.g., depression) that might independently prompt social withdrawal among people at elevated suicide risk [31, 32], it is plausible to expect natural social network dynamics will often result in the people at greatest risk being clustered together, with fewer connections at the periphery of their broader networks.

Since network structure is meaningfully connected to the suicide-related outcomes inside a given network, that same structure also has surprising potential as an intervention target. To see this, consider the following quantitative model of network evolution and a hypothetical intervention on its structure. Importantly, this model produces both of the real-world patterns described above (i.e., assortative clustering of risk, tendency toward isolation), but is also still simple enough that it can clarify and illustrate how underlying network processes can be targeted for intervention. This clarification function is a primary goal of such models, recognized by methodologists to be of parallel importance to more common goals like prediction [33, 34]. Thus, in

what follows, our model will clarify and illustrate how even relatively modest intervention to alter the structure of the networks can often dissolve stable high-risk clusters, as well as reduce overall rate of suicide risk in the network.

This model begins with a peer friendship network of 10 people. The social connections between them are assigned randomly. Three people are shaded dark gray, indicating that they have adopted attitudes and behaviors that place them at elevated risk for suicide. The remainder of people are shaded light gray, indicating they have adopted attitudes and behavior that place them at low risk for suicide. To incorporate the phenomenon of social influence highlighted above, at the beginning of each time point, every person considers what their friends were like at the last time point and attempts to adopt the state that most of their friends just had.2 They do so according to the following rules:

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of a randomly generated network that follows these rules. To walk the reader through that network’s evolution, note that the network is in a randomized configuration at time 1, which is analogous to people who might have just met in a new environment (e.g., in a new school or military unit). Then at time 2, Person A adopts increased risk, influenced by the 2/3 risk majority of E and G at time 1. Person J has only one friend (G), who happens to be at elevated risk, and J adopts elevated risk as a result of this 100% majority. Conversely, E’s adopts a healthy state, influenced by the 3/4 healthy majority of A, D, and H at time 1. Lastly, at time 3, A’s newly elevated risk from time 2 actually flips back into a healthy state, due to a new 2/3 healthy majority composed of E and I. After three time points, the simulated network is stable. Using the simplified rules above, no more changes are possible.

Although this model is an intentionally simplified version of real social network processes, it is nevertheless capable of reproducing the two major structural patterns related to suicide risk in social networks described above. First, the final network in Fig. 1 has stable assortative clustering. Each healthy person will stay healthy, supported by the healthpromoting influence of their majority-healthy friendships. In addition, similar to a real-world network, those with elevated risk are also stuck in a stable, risk-maintaining cluster at the edge of the network. In addition, similar to a real network, they have fewer average friends than their healthier peers near the network’s core.

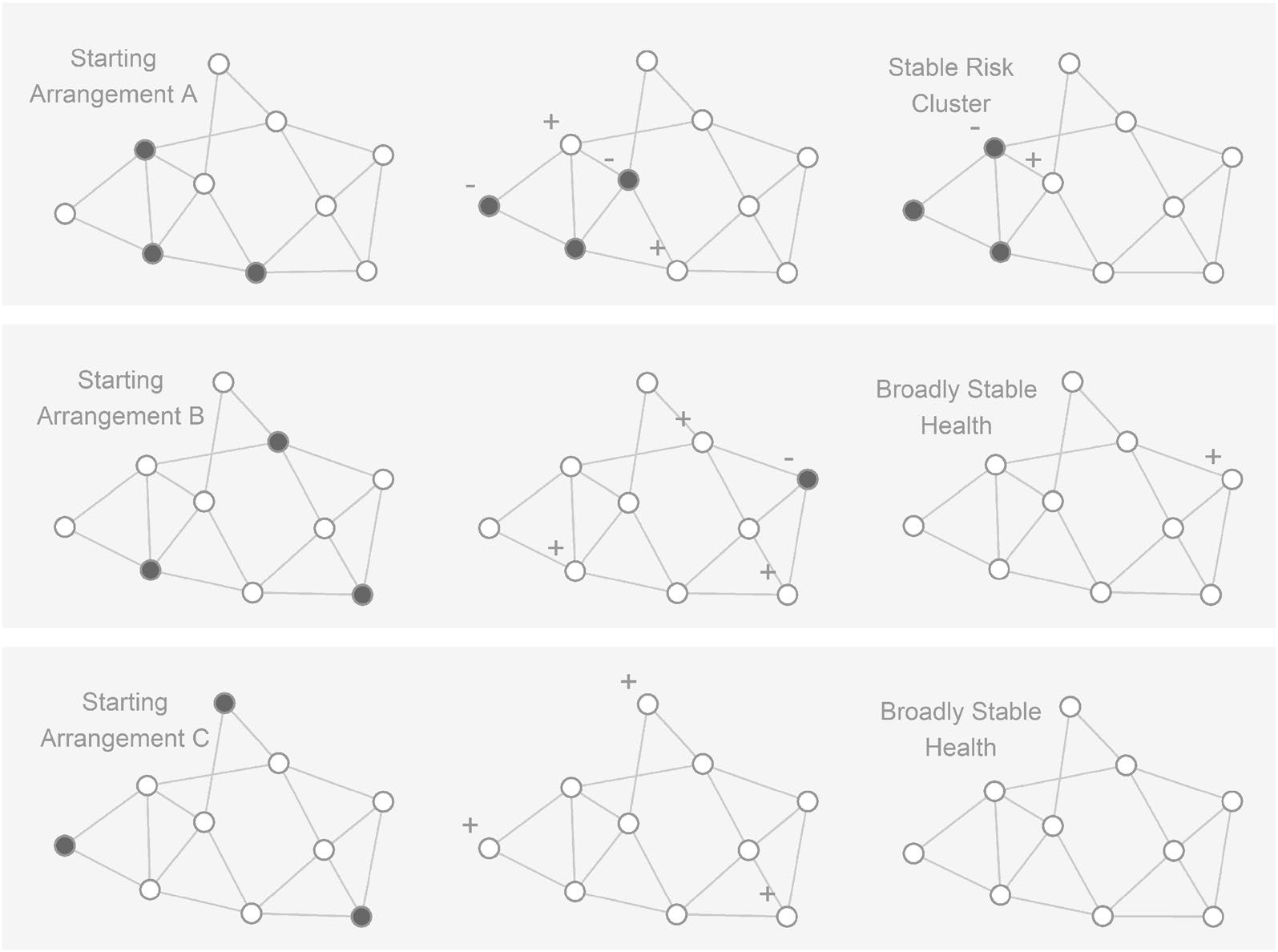

Could this network have evolved differently? Yes. The peripheral clustering of suicide risk is not the only possible outcome following our model’s simplified rules, nor is it always the case in the real world. First, different network structures can produce different outcomes. Second, even the same network can produce different outcomes, if the at-risk nodes are re-randomized to different starting conditions (see Fig. 2). However, what is important for this demonstration is that the overall distribution of outcomes still tends toward realism: either a network will exhibit no suicide risk at the end (i.e., be totally healthy like most small networks) or it will produce assortative clusters at the periphery. It is highly uncommon for this model to produce widespread suicide risk. In addition, although it is simplified, this distribution of outcomes is surprisingly informative for intervention development.

2 Note, it is of course unlikely an real person ‘chooses’ to be at elevated risk for suicide. But when describing this model and its results, we will say that someone ‘adopts a risky state’ or that they ‘adopt a healthy state’ for simplicity.

If this simplified model is an intuitive approximation of suicide risk evolution in real-world social networks, what kinds of interventions does it imply? Could those work in the real world too? We address both of these questions in order, saving the real-world empirical evidence for the final section. But here, we note two suicide-protective tendencies our model reveals about networks in which a majority of people are already healthy.

Fig. 2 Alternative outcomes for the same simulated network under different initial arrangements of suicide risk. The meaning of all symbols and process of network evolution are the same as in Fig. 1. Each horizontal panel depicts the same network (in terms of nodes and their connections), but with a different starting arrangement of which nodes are at elevated risk for suicide (the left-side networks). The networks evolve in discrete time steps, arrayed from left (earlier in time) to right (later in time). Although each of these different network arrangements evolve according to the same rules, their different starting configurations ultimately lead to different outcomes. After 3 time steps (the right-side networks), there is a stable risk cluster for Starting Arrangement A, but a total absence of suicide risk in Arrangements B and C.

First, when most people are already healthy, most of the connections between any two people will be health promoting. That is, they either continue to support an already healthy person’s health or they increase the likelihood an at-risk person will become healthy (even if that given connection is technically insufficient on its own). The same is true of the new connections that could be added to a given network can be expected to have the same properties. A majority of the connections that could be added will either bolster an already healthy person or they will promote the health of an at-risk person.

Second, note that because there are so many more healthy people in the network and because healthier people tend to have more friends, healthy clusters are on average more resistant to change than risky clusters. For this reason, any new connection between a random healthy person and a random at-risk person is more likely to help that at-risk person than it is to harm the healthy person. This is because a healthy person is still likely to have a majority-healthy group of friends, even if an at-risk person joins the group. In contrast, if even a single healthy person enters the social orbit of an at-risk person, that at-risk person’s immediate social circle is much more likely to become majority-healthy.

These two observations imply that interventions capable of altering the structure of a social network have surprising advantages for suicide prevention. First, because most people are healthy, and in turn, most new connections will thus be health promoting, even very basic interventions on network structure (e.g., simple addition of random connections) are likely to produce health-promoting connections at high rates. This can be achieved by relying on the general health of most people in the network, without ever identifying who is friends with whom, or who is currently at high risk. Second, because healthy clusters are more durable than risk clusters, structural interventions are also statistically likely to have greater benefit for those already at the greatest risk—a finding already observed empirically for a network intervention in the military. Third, the fact that healthy clusters are more durable than risky ones also suggests that structural interventions have an elevated probability of dissolving existing high-risk clusters that have already achieved stability. Said more directly, they are anti-clustering interventions.

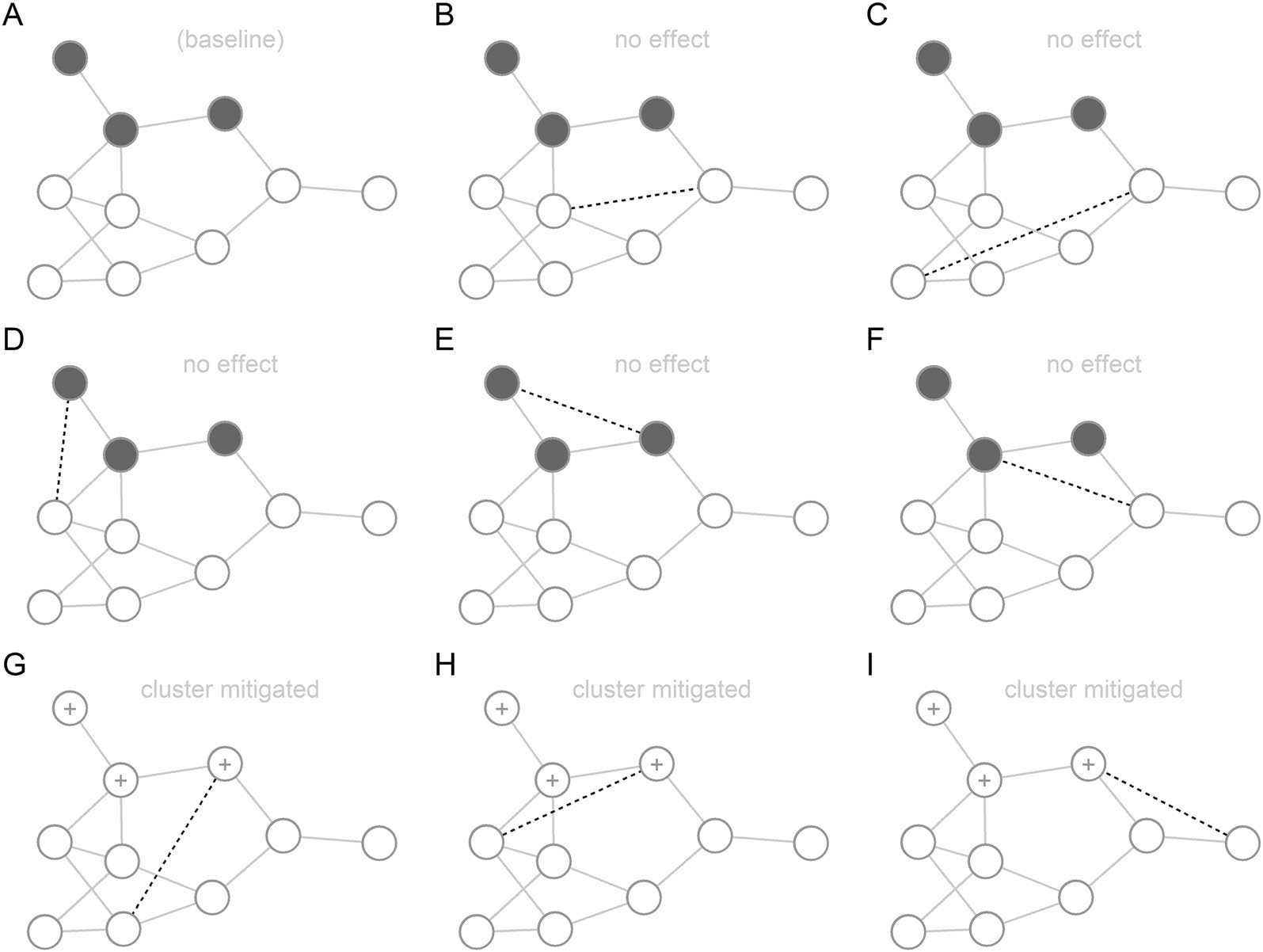

Fig. 3 Alternate possible outcomes for a hypothetical intervention that adds a single, randomly selected edge to an existing network. The meaning of all symbols and process of network evolution are the same as in Fig. 1. Dotted lines represent the edge being added by the intervention. Panel A represents a baseline network in a stable state, with no intervention implemented. Panels B through I show the long-term effects (i.e., after several time steps) of adding a particular edge (dotted line) to that baseline network in Panel A. This figure represents only an illustrative subset of all possible (n = 32) edges that could be added to the baseline network. Consistent with Panels B through I, most possible single-edge additions have now effect (81%), but a significant minority (19%) have mitigated the stability of the initial baseline risk cluster. This in turn has the subsequent, downstream effect of eliminating all risk from the network over time.

To demonstrate these three properties, we now implement a hypothetical intervention into our model. This intervention is especially simple, adding only a single randomly chosen connection (i.e., edge) to an existing network. What is the result? There are many possible edges that could be chosen, each with different possible outcomes. But note that what is important here is the average outcome. To explain, Fig. 3 illustrates the outcome of our intervention when applied to

an already stable network (specifically, the stabilized network from Fig. 1). In Panel A, the stable baseline network is shown (pre-intervention). Panels B through I depict the respective outcomes for that network, for a new edge added in 8 alternative locations. That is, they represent 8 different possible outcomes for our single-random-edge intervention.

As seen in the figure, many of the possible connections that could be randomly added by an intervention are between already healthy people (Panels B and C). Another group of additions is insufficient to dissolve the high-risk cluster alone (Panels D through F), even when they connect at-risk people to more healthy counterparts. Both of these cases result in no change to the risk profile of the network. However, several of the panels (G through I) also depict how adding a single random connection would not only resolve suicide risk for one person, but would also have the downstream effect of resolving the entire at-risk cluster over time.

That is, one person at the edge of the cluster improves due to a new healthy connection and becomes healthy. But this initial improvement implies that all of their friends now have an additional healthy friend as a result, shifting the social balance in favor of health for those downstream friends. When these downstream friends become healthy, they do the same for still more downstream friends, and so on. Thus, what was once a stable, self-reinforcing high-risk cluster is catalyzed toward health by only a small change in the network structure (i.e., a new tie to a healthy person) at the edge of that cluster.

For space, Fig. 3 only depicts a handful of all possible single-connection additions available for the base network in Panel A. However, if we calculate the results for every possible added edge individually (n = 32 connections total), results show that 19% of random additions will lead to fewer total at-risk nodes for the network after intervention. The remaining 81% produce no change in the risk profile of the network, and none of the single-edge additions produces any increase in at-risk risk nodes (in this case, though such outcomes are technically possible). This result illustrates how structural interventions can be generally safe, even when they are untargeted. They also illustrate that the plausible effect size is still modest, with only 1 in 5 single-edge additions producing a desirable improvement.

In response, we note that we only initially add one connection at a time in Fig. 3 to make the illustration simple for the reader. Most existing network interventions are likely to induce multiple new edges at once (e.g., by pairing several sets of people to have novel interactions with one another). What would the results look like for an intervention that added three random edges simultaneously? To answer this question, we re-ran the model, this time randomly choosing three edges to add to the network all at once. Results showed that of the 4960 possible combinations of three new edges, 57% resulted in a suicide reduction, 43% resulted in no change, and only 0.2% resulted in an increase in total risk in the network. Thus, while it is impossible to rule out the chance that random edge additions could mistakenly increase risk for a network, the probability of that happening is quite small due to the base rate of health in most networks. In addition, more importantly, the probability of successfully reducing suicide risk is quite high—even when nothing is known about the edges being added or the people that will receive them. It is thus likely that a more targeted intervention would show even greater promise by targeting network structure in a strategic way.

Taken together, these illustrative results are still far from a comprehensive simulation, but they nevertheless demonstrate the potential of interventions targeting network structure for suicide prevention. That is, even basic interventions are likely to help those at greatest risk, are unlikely to increase the risk of those who are already healthy, and have the capacity to resolve existing risk clusters in the process. That is, structural interventions can become cluster-resolving interventions.

The above model is intentionally simplified for the purpose of demonstration. With that in mind, it is worth asking whether there is any empirical support for (a) the responsiveness of real social networks to intervention and (b) whether such interventions have suicide-protective effects. Growing evidence suggests the answer to both is yes.

For example, the Wingman-Connect Program [35] is designed to enhance the natural social networks of early career Air Force members through a brief group-based intervention (6 h total distributed over three separate days). Through a facilitated process, members learn and model skills to each other for growing protective strengths that support adjustment to military life (i.e., stable social bonds, activities that promote psychological balance) and in doing so develop (often new and untargeted) connections to each other.

This intervention has now been tested in a large, cluster randomized trial with personnel in Air Force job training (N = 1485, average group size = 5–15). Consistent with the model simulations above, individuals already at elevated risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors became gradually more socially isolated over time in the active control condition (i.e., stress management training). In contrast, individuals at elevated risk in the Wingman-Connect condition demonstrated significant gains in nominated social connections from others, even though the intervention includes no content for targeting new connections (i.e., no instructions to seek out people at perceived risk). Specifically, at the end of the training program, 10% of elevated risk Airmen in the control condition were totally socially isolated from teammates, compared to 0% in the Wingman-Connect condition [36].

These improvements in social network structure were also associated with improvements in downstream outcomes. Wingman-Connect produced significant reductions in suicide risk scores, depression symptoms, and occupational problems compared to control [35]. Importantly, mediation analyses confirmed that these improvements through the hypothesized mechanism of increased belonging to more socially cohesive units, unified around healthy norms.

Although this area of research is still new, there is alsosupport for related interventions beyond Wingman-Connect as well. For example, an intervention aimed at strengthening social integration among all students in primary grade classrooms showed long-term impact on reducing suicide attempts through adolescence [37, 38]. Elsewhere, other interventions focused on strengthening connections among inter-generational social networks among students in high schools [11, 13] and youth discharging from acute psychiatric care following a suicide attempt also show promising for reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviors—possibly even mortality [10]. In addition, although results are not yet available, there are still more interventions and translations currently under development and evaluation [39].

The simplified model and related empirical findings offered above are meant to serve as an introduction to a new way of thinking about suicide prevention and motivation for further empirical investigation of that approach. However, we also note a few important caveats to help balance enthusiasm for both our model and the broader proposal with existing limitations and open questions. First, the model is intentionally simplified for clarity and, therefore, may be a poor approximation of more complex, real-world networks. Second, the model makes no distinction between different severities of suicidal phenomena (e.g., thoughts, attempts, and fatalities), and these may each respond to network interventions differently. Third, our results depend heavily on the assumption that most members of a network are relatively healthy, which is likely to hold in universal prevention contexts (e.g., schools), but may require more thoughtful application in acute settings (e.g., psychiatric inpatients). For example, Youth-nominated Support Teams is an excellent example of a mortality-reducing network intervention in an acute population, where the connections between trusted adults in a recently suicidal youth’s life are augmented (e.g., as opposed to enhanced connections with potentially distressed peers).

In addition to limitations, we also note important open questions. For example, how do we induce a relationship among two people who do not currently have one, or perhaps strengthen a relationship among existing acquaintances? Both long-standing basic research (e.g., the Minimal Group Paradigm [40, 41] and Fast Friends Procedure [42]) and the successful intervention examples above suggest it is possible to induce long-term affiliation, friendship, and mentorship in short periods of time. However, continued work to optimize these approaches—for both newly formed and longstanding social networks—should remain a high priority for future research. Second, additional research into intervention timing is also a high priority. For instance, the successful examples we cite above typically rely on new networks or networks that are expected to be in natural states of transition, but it is possible long-standing and stable networks may also benefit from structural interventions as well.

Lastly, perhaps the most important open question in this broader line of research involves the outlining of a formal theory of network enriching interventions (NEIs) for suicide prevention. It is possible existing network interventions for suicide may already implicitly manifest some of the features of such a theory, but we emphasize that explicit formalization of a pragmatic network theory of suicide prevention is likely an important next step for the optimization of emerging success, as well as translation to new groups and contexts.

In summary, the importance of social networks for suicide risk and protection is well established and foundational for the field of suicide prevention. Influenced by this knowledge, most existing interventions include at least some focus on strengthening social health. However, few interventions have intentionally focused on altering the structure of the social networks within which people are embedded, despite the unique effect of those network structures on suicide risk and protection (beyond individual- centered social perceptions). In contrast, we presented a developmental quantitative model to clarify the suicide

risk altering impact of an intervention targeting a single network feature—its connection structure. Results from this model suggest modifying network structure in even very basic ways (e.g., adding random connections) can have a significant, meaningful impact on the risk profile of people across entire social networks. Although intentionally simplified for clarity, this model was also still consistent with emerging empirical evidence suggesting that real-world interventions targeting various social networks (e.g., work training classes and peer friendship networks) are capable of influencing their structure and in doing so reduced risk of suicide-related outcomes. Suicide prevention would, therefore, benefit from investment in social network structures as an independent and important intervention target in their own right.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by a grant (KL2 TR001999) from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It was also supported by a National Institutes of Health Extramural Loan Repayment Award for Clinical Research (L30 MH120727).

Author contributions IC and PW conceived of the idea and wrote a majority of the manuscript. MDC also contributed to the writing process. IC prepared all figures and analysis code. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability All codes for creating simulated data and resulting

figures are available at osf.io/4vyw9.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Ethical approval No human subjects’ research was conducted.

Patient consent No human subjects’ research was conducted.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.