*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ian Cero, University of Rochester Medical Center, 300 Crittenden Blvd, Rochester, NY 14642. Email: ian_cero@urmc.rochester.edu

1. Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center, 300 Crittenden Blvd, Box PSYCH, Rochester, NY 14642, USA

2. Department of Medicine, The University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

3. Department of Public Health Sciences, The University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Ian Cero, ian_cero@urmc.rochester.edu

Peter Wyman, peter_wyman@urmc.rochester.edu

Ishanu Chattopadhyay, ishanu@uchicago.edu

Rober Gibbons, rgibbons1@bsd.uchicago.edu

This work was supported by a grant (KL2 TR001999) from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It was also supported by a National Institutes of Health Extramural Loan Repayment Award for Clinical Research (L30 MH120727). These funding sources had no direct input on the preparation of this manuscript.

The increasing standardization of suicide risk screening brings new challenges for the field of suicide prevention. Chief among these is ensuring that all the field’s predictive models (e.g., screeners, structured assessments, eRecord neural networks) balance not only accuracy, but also fairness for the different groups of people whose futures are being predicted (1). The growing field of algorithmic fairness (2,3) can help suicide prevention navigate these challenges.

Horowitz et al (this issue) highlight the complexity of fairness in suicide risk prediction.They found that the brief Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) (4) tool yielded high and equivalent sensitivity and specificity for suicide ideation across black and white youth in the emergency department. Confirmation that key accuracy metrics are equivalent across groups is significant. But even a predictive model with equal sensitivity and specificity will still paradoxically yield predictive disparities in the probability of false alarms, when applied to populations who have unequal base rates on the outcome being predicted.

Whenever base rates are uneven across groups, there is a mathematically unavoidable trade-off between different aspects of model accuracy (5). And because base rates are almost always uneven, the resulting predictive disparities can almost never be totally eliminated. They can only be thoughtfully traded between one type and another (5). The new challenge in suicide risk prediction is thus to make these trades in a way that optimizes predictive equity.

Optimal decisions about bail or early release rely on predictions for how likely the person seeking these outcomes is to engage in future criminal behavior. As in suicide risk prediction, this process increasingly involves standardized models. ProPublica recently analyzed over 10,000 of the actual predictions from a popular recidivism prediction model (COMPAS), finding clear evidence of racial bias (6). Black defendants were twice as likely as white defendants to receive a false positive classification – labeled “high risk”, when they would not actually go on to commit a future crime. In response, the creators of COMPAS presented equally compelling findings that the model’s overall classification accuracy (about 64%) was in fact equal for both black and white defendants (6). How can the model simultaneously produce biased false positive rates and equal overall prediction rates?

The paradoxical disparity in the COMPAS model is unlikely due to biased data, questions, or even the model. Instead, the predictive disparity is likely caused by uneven base rates on the outcome being predicted.(5) To explain, there are many important accuracy metrics for predictive models to maximize. The most popular are (a) sensitivity, (b) specificity, and (c) probability of false alarms (i.e., proportion of false positives over all test positives, equal to 1 – positive predictive value [PPV]).

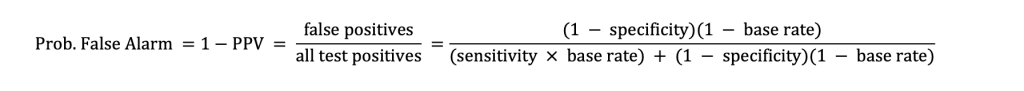

However, whenever the base rate of the outcome being predicted (e.g., suicide attempts) is uneven for two or more groups, a predictive disparity must manifest on at least one of these three metrics. For example, if an instrument has equal sensitivity and specificity across(1 − specificity)(1 − base rate) groups, uneven base rates will cause a predictive disparity in the probability of false alarms. And if the probability of false alarms is equal across groups, non-equivalent base rates will cause a disparity in either sensitivity or specificity. This unavoidable trade-off can be observed from theformula for probability of false alarms, itself:

As the derivation shows, whenever sensitivity and specificity remain the same, but the base rate changes (e.g., from group to group), the resulting probability of false alarms must also change.

Table 1 demonstrates the magnitude of the unavoidable trade-offs between accuracy metrics for a hypothetical suicide screener, applied to two hypothetical groups whose base rates differ on suicide attempts by only 1% to 4%. In this example, the sensitivity (.90) and specificity (.85) of the screener are held constant across the two groups. The uneven base rates thus cause a predictive disparity: more false alarms for the lower base rate group. Moreover, even in conditions where the base rate difference is small, the practical impact can still be large because suicide-related screeners are administered to many patients (e.g., in emergency departments). As illustrated in Table 1, even with base rates as similar as 5% versus 4%, only 25 people would need to be screened before an excess false alarm (i.e., disparity) was observed for the lower base rate group.

All predictive models make errors and all errors have costs. For even a false alarm on a suicide screener, the patient whose future was mis-predicted will often (a) pay a monetary fee for unnecessary follow-up, (b) and potentially a cost of lost trust in the provider – an issue especially salient for historically marginalized communities health systems already struggle to serve.1 Thoughtful screening pipelines can shift the timing and location of these costs, but they do not automatically eliminate the underlying predictive disparity trade-offs (7). That is, because such pipelines are ultimately just a predictive model with more steps, they face the same inherent trades – even if those trades are harder to see.

The growing field of algorithmic fairness (2,3) proposes that a model’s fairness can be measured by how far it deviates from equally accurate prediction across any metric of interest.

1. An argument is sometimes made that anyone screening positive on of a suicide instrument must have some mental health concern in need of follow-up. Although some patients with false alarm screens may also have an additional mental health concern in need of follow-up, it necessarily follows from a non-zero false alarm rate that a significant portion of them would still pay unnecessary costs for that same follow up.

2. To be clear, there is still debate over many different definitions of predictive fairness, but most of them center on this theme, which is sufficient for the current discussion.As an example, in Table 1, we would say that fairness is high, when the false alarm disparity is low. Fortunately, the trade-off between accuracy and fairness is rarely one-to-one (8). It is sometimes possible to trade a smaller amount of accuracy to gain much greater fairness, or to trade some fairness to gain much greater accuracy. The future of predictive fairness is thus not in rote maximization of either fairness or accuracy. The future is instead in identifying the most equitable trades: (a) those that lose the least and gain the most and (b) those that are aligned with the values of the community utilizing the model.

Base rates for suicide-related outcomes vary markedly across groups (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, age) (9,10). Although those rates have been lower among some historically marginalized groups, this paradoxically implies that those groups experience a higher probability of false alarms from risk prediction models. They will thus also pay a disproportionate share of the costs from those models’ errors.

A new commitment is needed to large scale and prospectively designed studies that investigate the full scope of this problem and the optimal alternatives, beyond just what is currently possible with existing secondary data sources. These new studies must address not only traditional measures of cost (e.g., money, time to patients), but also new and more inclusive measures of screening mistakes (e.g., eroded community trust in healthcare systems), as well as community stakeholders’ preferences for different types of trade-offs and solutions.

In practice, suicide prevention can begin this new program of research, informed by progress already made in the evolving field of algorithmic fairness. For example, there are now methods for fitting predictive models constrained by a “fairness budget,” which identify the most accurate cut score achieving at least a minimum of fairness (11,12). There are also survey methods for eliciting desirable fairness trades from community members (e.g., patients, providers), which can be used to train a model to select an optimal cut score consistent with the values of that community (8). As fairness tools develop, we thus advocate the development of new best practices in the predictive modelling of suicide risk. These practices should include not only optimization accuracy, but also fairness.

Lastly, additional work is needed to develop practice guidelines for individual clinicians working with individual patients. Importantly, those guidelines should follow directly from the prospective research studies outlined above, which are unfortunately still in early stages. In the meantime, we caution against individual clinicians making “ad hoc” adjustments to screening and risk thresholds (e.g., intuitively adjusting previously standardized cut scores for different demographic groups), which could introduce unintended negative consequences. Instead, while still waiting for systematic research-informed guidance, productive interim activities for clinicians could include seeking clinic policy changes that reduce the burden of errors for all patients.

Dr Gibbons reported being a founder of Adaptive Testing Technologies and sharing intellectual property rights for the Computerized Adaptive Screen for Suicidal Youth, both outside the submitted work.

The remaining authors report no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

1. Coley RY, Johnson E, Simon GE, Cruz M, Shortreed SM. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Performance of Prediction Models for Death by Suicide After Mental Health Visits. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 1;78(7):726–34.

2. Kearns M, Roth A. The ethical algorithm: The science of socially aware algorithm design. Oxford University Press; 2019.

3. Wang X, Zhang Y, Zhu R. A brief review on algorithmic fairness. Manag Syst Eng. 2022 Nov 10;1(1):7.

4. Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, Ballard E, Klima J, Rosenstein DL, et al. Ask Suicide- Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1170–6.

5. Kleinberg J, Mullainathan S, Raghavan M. Inherent Trade-Offs in the Fair Determination of Risk Scores. ArXiv160905807 Cs Stat [Internet]. 2016 Nov 17 [cited 2019 Nov 6]; Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05807

6. Larson J, Mattu S, Kirchner L, Angwin J. How We Analyzed the COMPAS Recidivism Algorithm [Internet]. ProPublica. 2016 [cited 2022 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.propublica.org/article/how-we-analyzed-the-compas-recidivism-algorithm

7. Bakker M, Valdes HR, Tu DP, Gummadi KP, Varshney KR, Weller A, et al. Fair Enough: Improving Fairness in Budget-Constrained Decision Making Using Confidence Thresholds.

8. Jung C, Kearns M, Neel S, Roth A, Stapleton L, Wu ZS. An Algorithmic Framework for Fairness Elicitation [Internet]. arXiv; 2020 [cited 2022 Oct 27]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.10660

9. Xiao Y, Cerel J, Mann JJ. Temporal Trends in Suicidal Ideation and Attempts Among US Adolescents by Sex and Race/Ethnicity, 1991-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Jun 14;4(6):e2113513.

10. Capistrant BD, Nakash O. Suicide Risk for Sexual Minorities in Middle and Older Age: Evidence From the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019 May 1;27(5):559–63.

11. Zafar MB, Valera I, Rodriguez MG, Gummadi KP. Fairness Constraints: Mechanisms for Fair Classification [Internet]. arXiv; 2017 [cited 2022 Dec 30]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1507.05259

12. Dwork C, Hardt M, Pitassi T, Reingold O, Zemel R. Fairness through awareness. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference on – ITCS ’12 [Internet]. Cambridge, Massachusetts: ACM Press; 2012 [cited 2022 Dec 30]. p. 214–26. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2090236.2090255

Table 1. Excess false positives for a hypothetical suicide screener (sensitivity = .90, specificity = .85) administered to two groups with uneven suicide attempt base rates

| Attempt base rate | Prob. false alarm | Attempt base rate | Prob. false alarm | Excess false alarms | Screens needed for disparity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 76% | 5% | 76% | 0% | -- |

| 5% | 76% | 4% | 8% | 4% | 25.0 |

| 5% | 76% | 3% | 84% | 8% | 12.0 |

| 5% | 76% | 2% | 89% | 13% | 7.6 |

| 5% | 76% | 1% | 94% | 18% | 5.5 |

Note. This example assumes a screening instrument that has equal sensitivity (.90) and specificity (.85) for both groups. Prob. false alarm = false positives / all test positives = 1 – positive predictive value (PPV). Screens needed for disparity is calculated as 1/(excess false alarms) and represents how many people from Group B would need to be screened before an extra false positive screen is produced (i.e., a false positive that would not have been expected if that same person were a member of Group A).